A Supreme Effort: Saving the Belknap Mill

The early 1970s was a perilous time for the old mill buildings on Beacon Street in downtown Laconia. The buildings were no longer used, and the rooms were empty and dusty. If you were to walk through the structures, you might imagine hearing the ghostly call of one former mill worker to another or the noise of the textile machines.

By 1969, the Belknap Mill closed its doors, a victim of changing times and a world that no longer needed the old ways of manufacturing. All around the downtown area, buildings were demolished as the trend for replacing the old with the new took over. There seemed to be less regard for a building with history attached to it, especially for the area’s old mill structures.

However, not everyone saw it that way. A group of Laconia citizens must have been distressed to see the former downtown Laconia they knew and, in some cases, grew up with being torn down to make way for a parking garage, parking lots, and modern buildings. Those who saw a need to preserve the past may have asked themselves if there was a way to retain at least a few buildings, specifically the two former mill buildings on Beacon Street.

Today, we would look at the Belknap Mill and adjacent Busiel Mill buildings and recognize their architectural beauty. But in the early 1970s, many viewed the mills as an eyesore and saw no purpose in rescuing the brick buildings. An article in the Laconia Evening Citizen, dated October 23, 1970, was an ominous prediction of future things. The headline read “Mill Disposal Deadline Set.” The Laconia Redevelopment and Housing Authority reported to the Mayor and city council that unless funds and plans were forthcoming, the Seeburg and Belknap-Sulloway mills would be torn down by June 1, 1971.

It is worth noting the article also mentioned the status of the Belknap Mill, which was reserved for museum use. It was warned, however, that plans and funds would be needed by March 1, 1971, or demolition would begin on June 1.

Luckily, there were those already meeting and working to save the old mills. At the first annual meeting of the Save the Mill Society, President Richard Davis reported that for the first time, the National Trust for Historic Preservation contributed toward preserving something other than a presidential residence. The amount given was $500 to go toward preserving the Belknap Sulloway and Busiel mills. It was the hope and goal of the Mill Society that the buildings would be placed on the National Register in Washington, which would be impactful in the goal of saving the mills.

Despite efforts to keep the mills from demolition, deadlines were looming. An article in the Laconia Evening Citizen from December 26, 1970, reported that the Laconia Housing and Redevelopment Authority set a firm deadline of June 1, 1971, to decide on the fate of the buildings. The efforts to save the mills did not go unnoticed; the buildings had been under consideration at the time in connection with the Urban Renewal project. Ideas for the mills were restoration as a city hall and the Belknap Mill specifically for use as a museum and cultural center.

Housing Authority chairman Richard A. Messer said, “In essence, what the authority advised … was what steps will have to be taken to demolish the mills if no development proposals assuring their rehabilitation for private or public use are firmed up by next June 1.” Whether one agreed with the feeling of saving the mills or tearing them down, all seemed to agree there should be a good look at the structural condition of the buildings and the work required to bring the mills up to local code standards.

A Save the Mill committee report on December 21, 1970, stated that the members were meeting each Friday at noon for lunch to keep up with current trends and plan for necessary work. The committee was about to continue its dedicated efforts to preserve the mills. There would have been distress and a sense of urgency among the committee members when they were informed that the Planning Board of Laconia had altered the schedule to hear plans for using the Belknap Mill by March 1. The new plan was to demolish the mill buildings – immediately.

Swinging into action, the Mill committee decided to attend a meeting in the Mayor’s office that evening to protest and lay out their plans for Mill renovations. They would also meet with the Chamber of Commerce that very afternoon.

In the same report, Dorothy Buley presented a possible plan for a museum and restaurant for the Belknap Mill. She wrote that the Mill museum would not be a tale of early elegant homes like those found around Portsmouth’s Strawbery Banke or a display of local farming. In capital letters, she wrote that a Mill museum would be THE STORY OF THE LAKES REGION AND THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION.

A centerpiece for the proposed museum would be a display of the country’s oldest untouched brick mill building. The story of weaving fabric for Civil War uniforms and the knitting of socks, both done at the mill, would be included in the displays.

According to Buley’s report, a restaurant would also be possible. The dining establishment would use antique mill equipment and other items for decoration, and even the dining tables would have lighted, locked displays on the tabletops. It was a creative and worthy idea, but not all (such as a Mill restaurant) came to fruition; only the museum plan became a part of the finished Belknap Mill.

No doubt dedicated Save the Mill members were committed to saving the mills. Their work was tireless, particularly the efforts of Peter Karagianis, a Laconia businessman and citizen who saw the eventual saving of the mill completed. But it was a long road with many meetings, trips to give reports, and constant efforts to obtain funding for building renovations.

Today, as the Belknap Mill’s annual meeting is upon us, it is worthwhile to look back on the early days of the Save the Mill effort. The early 1970s were a time of embracing the modern and new, while others wanted to move forward but preserve the history of the community. These herculean preservation goals created the brick mill buildings we see before us today.

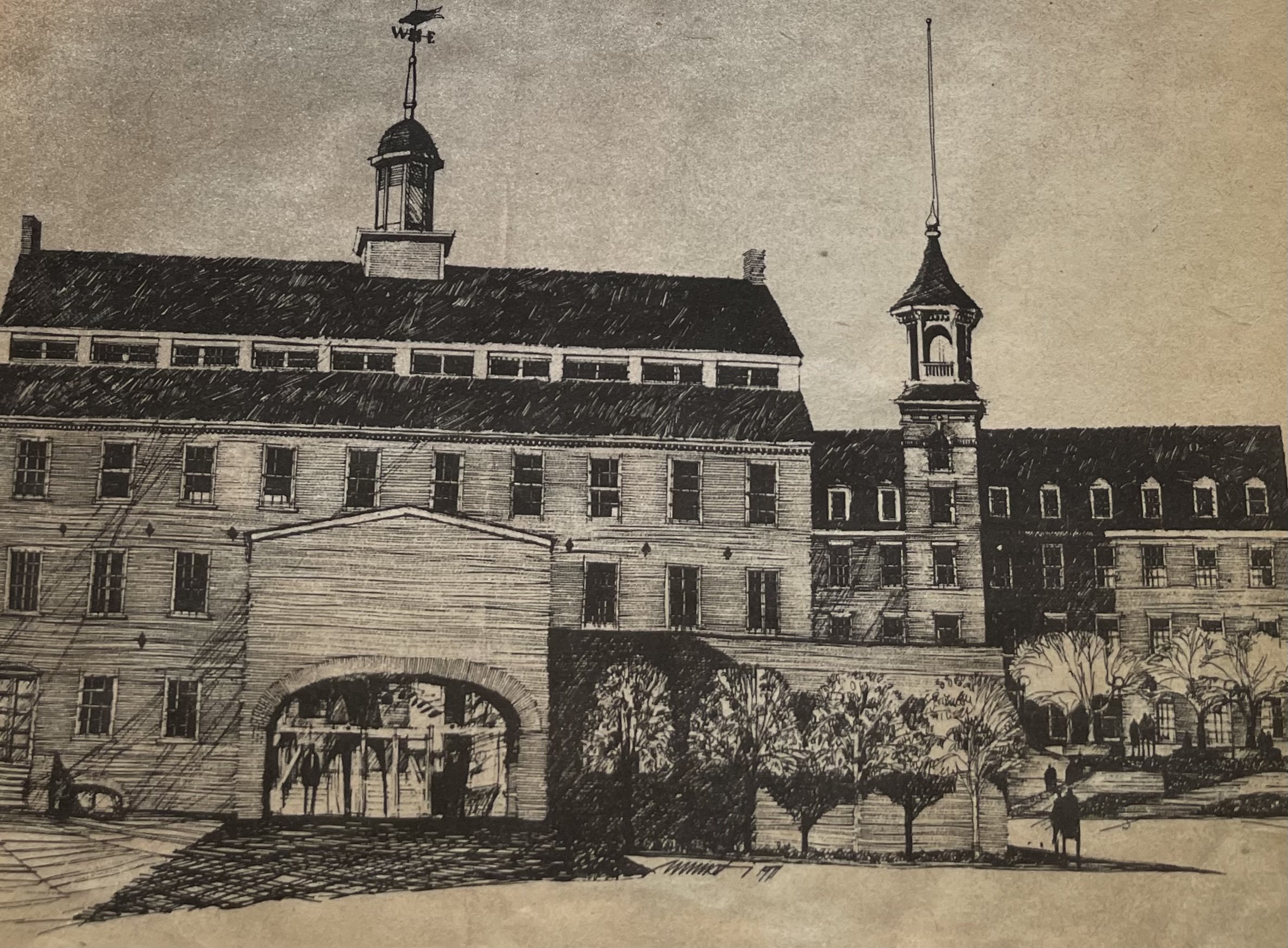

A rendering of the Belknap Mill may have been created to display plans for the renovated structure.

(Belknap Mill collection; artist unknown)

Women Mill workers in Laconia.

(Belknap Mill collection)

Historic photo of the old Belknap Mill complex and area.

(Belknap Mill collection)

Peter Karagianis, a major player in the effort to save the Belknap Mill (standing at right) looks on as

children and others examine a Belknap Mill bell replica.

(Belknap Mill collection)